Timeline of Boscobel History

Learn about the fascinating people and cultural movements that contributed to Boscobel’s dramatic history.

1700s

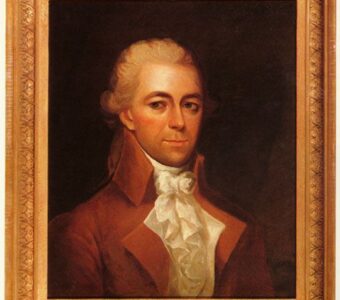

1755: States Morris Dyckman is Born

States Morris Dyckman was born on Manhattan Island to Jacob Dyckman and Catalina Benson in 1755. He belongs to the fourth generation descending from one of the earliest settlers of New Amsterdam (now Manhattan), Jan Dyckman, who arrived from Westphalia in 1662. The Dyckman family amassed large land holdings in northern Manhattan, including parts of Central Park and today’s Inwood neighborhood, once a thriving homeland of the Lenape people. Farming and cider production helped the Dyckmans secure generational wealth, as did their reliance on enslaved labor at home and in the fields.

States’s father failed at various business ventures and died young, sparking in young States an ambition to secure his own financial and social position. He trained as a clerk, and began working for the British Colonial government in Albany. Only age 21 in 1776 when war erupted, he declared his allegiance to King George III, convinced that remaining British was the most likely path to prosperity for himself, and for America.

1776: Elizabeth Corne Kennedy is Born

In 1776, States Dyckman was imprisoned for toasting to King George III, then allowed to flee to Manhattan to join fellow Loyalists and the British troops stationed there. That same year his future wife, Elizabeth Corné Kennedy, was born in 1776 to Dennis Kennedy and Letitia Corné. For reasons not clear, Elizabeth was raised by her grandfather, Peter Corné, a sea captain who became wealthy trading enslaved people from Africa.

Born in Scotland, Corné was a staunch Loyalist during and after the American Revolution in spite of suffering property seizure, fines, imprisonment, and exile. Corné raised Elizabeth in Peekskill, where States Dyckman would later purchase a farm, King’s Grange. Corné and Dyckman were both members St. Philip’s Church (now in Garrison); the Anglican faith bound many Hudson Valley colonists and Great Britain.

1776-1779: Loyalist States Dyckman Serves the British Army

After war broke out and he lost his post in Albany, States fled to Manhattan and became a clerk for the British Army’s Quartermaster Department. The quartermasters were responsible for providing all of the necessary provisions and supplies to the British army. States was in charge of keeping their accounts. His local connections would have been useful to the British needing to source provisions, horses, wagons, and other supplies; and to the locals desperate to stay solvent through the conflict.

Like New York, the Dyckman family’s allegiances were fairly evenly split: States’s closest sibling, his brother Sampson, joined the Patriot cause, serving as one of General Washington’s most trusted personal couriers. This division helped ensure that no matter the war’s outcome, there would be Dyckmans in a position to help their less fortunate counterparts.

1779-1789: States Travels to England to Assist Quartermaster General

When the Quartermaster General, Sir William Erskine, was recalled to London in 1779 for a government audit of his accounts, he asked States to accompany him. Dyckman ended up spending ten years in London, 1779-1789, working for Erskine and several other quartermasters who were under investigation by the British government for profiteering during the Revolutionary War. They were cleared of the charges and, as a reward for his services, States was paid very well by Sir William and other members of the Quartermaster Department. These travels and the exposure to finer things proved formative.

1789: States Returns to New York, Becomes a Gentleman Farmer

After being assured that it was safe for Loyalists to return, States Dyckman sailed back to New York in 1789, settling at his Kings Ferry farm overlooking the Hudson at the Haverstraw Bay. With the interest from an annuity set up by Sir William Erskine and the income from other investments, States expected, in the words of his biographer James Flexner, to live as a “conspicuously well-fixed farmer, surrounded with objects of taste…who did not farm too seriously.”

1793: Overspending Puts Finances at Risk

The residual pay-offs from Dyckman’s service to the Quartermasters were enormous. Still, Dyckman managed to drain the fortune through extravagant spending abroad and at home, and by supporting various family members, on both sides, who had suffered wartime losses. In 1793 he was forced to sell to Chancellor Robert R. Livingston one of his prized possessions: the library of 1,400 leather-bound books he acquired while in London (many of these have been reunited at Boscobel). That same year States began courting Elizabeth, the granddaughter and ward of his wealthy neighbor Peter Corné. States met Corné’s strict requirements related to politics and religion, barely superseding concerns over States’s volatile finances and the couple’s 20-year age gap.

1794: A Happy Union, States and Elizabeth Dyckman

States and Elizabeth married on February 1, 1794. He was thirty-nine and she was eighteen at the time of their marriage. Together they had two children, Peter Corné Dyckman, who was born in 1797 and Letitia Catalina, who was born in 1799 and died as an infant.

States is said to have brought into the marriage an enslaved African American woman named Sarah Wilkinson, nicknamed “Sil,” who worked as the family cook for at least three decades.

Research is ongoing to find out more about Wilkinson and the extended Dyckman family’s economic network in Westchester and Manhattan, and the broader context of slavery and indentured servitude in New York. Boscobel is a founding member of the Northern Slavery Collective along with the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum, a “cousin” site and the oldest extent farmhouse in Manhattan.

1795: Death of Benefactor Brings More Financial Difficulties

States’s benefactor, Sir William Erskine, died in 1795. Soon after, Erskine’s heirs halted payment on the annuity that Erskine had promised and the Dyckman’s situation became precarious. In 1799 with money borrowed from Elizabeth’s family, States left his wife and two young children and returned to England in hopes of reclaiming his lost income.

Baby Letitia died from a yellow fever outbreak shortly after States sailed; it took several months for the news to reach him. Elizabeth credited Sil, the enslaved cook, for nursing the family. In her letter to States, Elisabeth described “dear Sil, the kindest and most affectionate of mothers has she been to me and my children in all our Distress.”

1800s

1800-1803: States Returns to England to Reclaim his Annuity

States had expected to complete his business and return from London within the year. While there, he agreed to assist General John Dalrymple, the last of the quartermasters under investigation for wartime profiteering. States remained in London for three years. During that time he managed to have his annuity resumed by the Erskine family, and received a large settlement from Dalrymple and the other quartermasters he had previously aided.

These funds were not provided willingly and voluntarily. States was forced to threaten his noble clients with exposure. Above the annuity and other financial considerations, he received an additional 12,000 pounds in payments (worth more than $2 million today). In return for these payments, States agreed to destroy all of the records that he had used to document and defend the quartermasters’ accounts before the Treasury Department’s Committee of Investigation, documents that could conceivably have been used to incriminate the quartermasters if the investigation was reopened.

1800-1803: Shopping for the Best of the Best

While in England, States shopped at many of the finest and most fashionable shops in London to purchase trees and plants, housewares, decorative objects, clothing, and personal gifts to send back to Elizabeth and their farm. Concerned about his and his wife’s reputation and status, he wrote to Elizabeth:

“I now send my dear Love by Captn Webb the things I mentioned in my last, with some additions, you will be surprised to find them so expensive, but exclusive of the happiness I have in contributing to yours, I have another. It is simply this. I do not wish that your malicious neighbors or even an Acquaintance in Town, should trace in your appearance too plainly the cause of my leaving you. Therefore I wish you not only to have these presents to show but to wear.” (States Dyckman to Elizabeth, September 1, 1800)

Elizabeth replied with gratitude, yet encouraged him to be more frugal, and above all, to return home as soon as possible.

1800-1803: Boscobel Manor in England, An Idea is Born

While in England, States traveled extensively, visiting among other places the original Boscobel estate in Shropshire, England. This estate was well-known as the site where King Charles II went hid in an oak tree after his defeat by Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. Later, after the crown was restored to the king’s name, the story of the day the king spent in the forest at Boscobel Manor became legend and the Royal Oak became a popular symbol of the monarchy.

It is from here that States Dyckman chose the name Boscobel for his future Hudson Valley estate. It can be presumed that he thought it as his own personal refuge from the years of legal battles to obtain moneys owed to him by the English generals he served during the war. It is likely that the name “Boscobel”, had a more significant meaning than its general translation from the Italian “beautiful woods or forest.”

1803: Return to America with a Dream of Boscobel

States Dyckman returned to America in late 1803. He was ill from persistent attacks of gout and the lingering effects of a leg injury he sustained in a carriage accident. Nevertheless, he was determined to build his dream mansion overlooking the Hudson on the 250-acre farm he owned in Montrose, New York.

The house would serve as a tangible symbol of his prosperity and social status and as an expression of his refined taste. He also wanted it to become a permanent country seat that would be inherited by his son and remain with future generations of the Dyckman family.

1804: Construction Begins

Construction began in the summer of 1804. Although no architect has been identified for the building, it has long been considered to be an outstanding example of Federal domestic architecture in America. One can assume that States was influenced by what he had seen in England, particularly the designs of Robert Adam (1728-1792) and his contemporaries. It is possible that he had the architectural plans for his new house drawn in England since construction was started in the summer of 1804, a mere six months after his return to the Hudson River Valley.

1806: States Falls Ill, Does Not Live to See his Dream Realized

Sadly, States’ chronic illness caught up with him, and he died two years later in August, 1806 at the age of fifty-one. At that time, only the foundation for his new house was completed. His widow Elizabeth took over the project with the assistance of master builder William Vermillyea.

1808: A House Complete

Construction was completed and Elizabeth moved into the residence in 1808 with their only surviving child, Peter Corne Dyckman (1797-1824). Elizabeth furnished the house in a manner suited to the decorative accessories that States had sent from England five years earlier. Elizabeth purchased furniture, carpeting and other home goods from New York area designers, artisans and manufacturers of the time. When she was finished, the exquisiteness of the decorative accessories set Boscobel apart from other mansions of the day. For example, in an 1808 assessment, the well-known van Cortland family, whose estate was nearby, was valued at $27,000, with $25,000 from real estate and $2,000 from personal possessions, including the furnishings at Van Cortland Manor House in Croton. Elizabeth’s assessment was quite different, with her real estate assessed at $12,000 and her personal property, including all furnishings and decorative arts, from $8,000-10,000.

1808-1823: Life at Boscobel

Although Elizabeth was among Westchester County’s wealthiest women with several servants, she did not live a life of leisure. She supervised all work in the household and kept track of the farm work, joining in when needed. A household the size of Boscobel, especially one filled with fine furniture and decorative accessories from New York and England, required constant care and attention. Boscobel was not, however, a showplace. It was a working farm of 250 acres and it was Elizabeth’s job to make sure that the farm prospered. The farm had chickens, geese, and turkeys. Each years they raised hogs, which became bacon, ham and pork that formed the mainstay of their diet. The pastures surrounding Boscobel supported cows for milk as well as young steer to be trained as oxen to pull ploughs through the fields. Horses for draft and for riding shared the pasture. Elizabeth also raised sheep (she had 61 in 1806) as they were an important source of food and wool.

1808-1823: Life at Boscobel, Farm crops

In terms of crops, corn, rye and wheat, and to a lesser extent, oats, buckwheat and millet were grown. Fruit trees imported from Europe (by States) guaranteed a supply of fresh fruit. The household benefited from a plentiful supply of fresh apples, pears, cherries, apricots and peaches. They also provided a supply to make dried fruit, jams and jellies, and ciders that could be stored and consumed throughout the year.

1808-1823: Life at Boscobel, The Garden

One other key element of the Boscobel property was the garden. This area, located near the house was frequently referred to as the “kitchen garden”. Elizabeth Dyckman’s garden at Boscobel produced a variety of vegetables including parsnips, beets, carrots, radishes, turnips, leafy greens, asparagus, beans and peas. Also important was the herb garden, which served culinary and medicinal purposes as well as the plants used to produce dyes for textiles.

1808-1823: Life at Boscobel, The Household

During these years, the household at Boscobel was made up of Elizabeth, Peter, his wife, Susan Matilda Whetten, (married in 1819), a small group of live-in servants and a steady stream of daily, weekly and monthly farm laborers who were hired as needed. According to the 1810 census, Elizabeth Dyckman’s in-house staff included four freed slaves –two adults and two children. Sarah Wilkinson, affectionately known to the family as Sill, had been listed in the 1800 census as a slave to States Dyckman’s bachelor household. In the 1810 census Sill and her husband George were listed as freed. Sill was the primary servant and cook and her husband George worked the farm. They had three children who also helped around the house. Sill stayed with the family for several decades. Records also show that at various time several young women who were probably relatives or children of neighbors learning skills necessary to run their own households also lived at Boscobel.

1823 & 1824: Death of Elizabeth Dyckman and Year Later, Peter Corne Dyckman

Elizabeth Dyckman died on July 28, 1823 at the age 47. Less than one year later, on April 20, 1824, her son Peter died at the age 27. Peter’s wife Susan and their daughter Eliza Letitia remained at Boscobel. Descendants of States and Elizabeth Dyckman continued to live at the house for over another 60 years.

1888: Dyckman Ownership Comes to an End

Boscobel remained in the Dyckman family until 1888. From that time until 1923, the house was owned by a succession of private parties until the Westchester County Parks Commission acquired the land, and the house, for public use.

1900s

1923: Westchester County acquires Boscobel to Create Crugers Park

The Westchester County Parks acquired the property in 1923. The house, however, was not restored and remained vacant.

1930s: Blessing in Disguise

After eight more years of neglect, an unexpected benefit came upon the house as a result of the Great Depression, one of the first in a series of steps that would prove critical to the existence of Boscobel today. In 1932 a team of three architects from the Westchester County Emergency Works Bureau was assigned to document the building and its interior features in a project that predated the Historic American Building Survey, which was established a year later. William Sterzbach, Paul Luther Wood and John C. Merrill measured the house and made scale drawings of floor plans, elevations, and sections of the house. The men were so enthralled with the “superb workmanship and materials of the old house” that they produced measured drawings and photographs of scores of details of plaster ceiling ornaments, mantelpieces, the staircase, architectural woodwork, and molding profiles. These drawings would serve as the basis for the authentic restoration of lost elements years later. The County’s effort to document the house was surely motivated by a sense that it was unable to maintain the house much less restore it, but their efforts were later appreciated nonetheless!

1941: Westchester County Threatens to Raze Boscobel

In December, 1941, the Westchester County Parks Commission threatened to demolish the building.

1942: Local Citizens Unite for the Preservation of Boscobel

Local citizens, led by Beaux-arts trained architect Harvey Stevenson, formed Boscobel, Inc. to fight the threat to what was already being recognized as one of the nation’s premier “Early American” houses. This newly-formed group attained a five-year lease for Boscobel and became the caretaker of the mansion. With the nation at war however, fundraising for the necessary repairs and maintenance was difficult to initiate.

1945: Veteran’s Administration Acquire Property for Hospital

The property was acquired by the Veteran’s Administration for the construction of a new hospital, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Veteran’s Administration Hospital, which is there to this day. Thirty-two modern brick buildings were constructed on a 385-acre tract of land surrounding the house. The house remained in a state of disrepair.

1954: Boscobel Declared to be “Excess” and Slated for Demolition

After recurrent efforts to persuade the government to restore Boscobel for use as a guest house or administration building for the hospital, the General Services Administration could not find a suitable use for the building and declared Boscobel house to be “excess to the needs of the Veteran’s Administration.”

1955: Boscobel Sold to the Wreckers for $35

In January 1955, Boscobel was put up for auction and purchased by a demolition contractor. There were two bids, one for $10 and the winning bid for $35.

Before the building was demolished certain key elements, such as the celebrated front facade and many other exterior and interior architectural details, were sold and removed to be used in a new house being built on Long Island by Mrs. Henry P. Davison.

1955: Local Citizens Lead a Dramatic Rescue

A new organization, Boscobel Restoration, Inc., is created to save the building and in a dramatic, down-to-the-last-minute effort led by Benjamin West Frazier, then President of the Putnam County Historical Society, enough funds were raised and paperwork signed to stop the demolition and acquire the remaining portions of the structure.

1956: A Benefactor of Significant Proportions

In 1956 a tract of land came on the market in Garrison, just as Boscobel Restoration was trying to find a suitable place to reconstruct the mansion. The property, 16 acres of rolling land with sweeping views of the Hudson River, West Point and Constitution Island was being sold as an estate. An originally-anonymous donation of $50,000 by Mrs. Lila Acheson Wallace, co-founder of Reader’s Digest, received in June 1956 allowed the newly incorporated Boscobel Restoration, Inc. to acquire the property and begin the restoration.

1956: A House on the Move

Over a five-month period, the house was dismantled and moved piece-by-piece to Garrison, where the pieces were stored in barns and other vacant buildings.

But for the project to succeed, it was essential that the original decorative woodwork sold to Mrs. Davison be reclaimed. It proved difficult to raise funds for the restoration of the house when the original architectural elements, including the unique swags from the front facade, were absent. The new owner of the original elements was willing to cooperate. She generously agreed to return them, retaining only the items already installed in her new house, on the condition that copies were made in exchange.

1957-1960: Putting the Pieces Back Together

The restoration of Boscobel commenced in March, 1957 with Harvey Stevenson serving as architect of the project and Lt. Col. M. Campbell Lorini as Restoration Project Coordinator. Stevenson was fortunate to have the Historic American Building Survey plans from decades earlier to work from, but he and the board made modifications to the plans in ways they felt did not adversely affect the architectural significance of the house. For instance, the side decks were enlarged and the historic basement spaces were not included and were instead replaced with meeting rooms and catering facilities.

1959: The Lila Wallace Touch, The Landscape

In addition to her financial backing, Mrs. Wallace served on the board of directors and took a strong personal interest in the restoration of Boscobel. She was particularly influential in the landscaping of the grounds and the furnishing and decorating of the interiors.

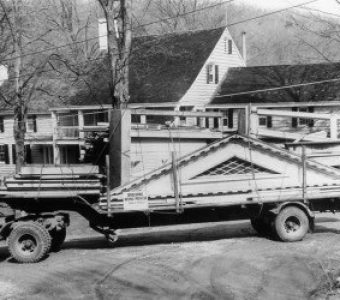

In 1959, she brought in the highly-regarded (and today historically significant) landscape architectural firm of Innocenti and Webel to provide an appropriate historical setting for the restored house. Richard K. Webel’s landscape plan for Boscobel bears little resemblance to its original site in Montrose. He proposed a classically-inspired landscape in the Beaux-Arts style popular from the turn of the century to the mid-1930s. This style was meant to provide an appropriate setting to complement the formal architecture of the house. The firm specialized in transplanting large trees using a newly developed technique for digging larger holes around trees and protecting their roots and moving a large soil mass with them. Giant maples, mature shrubs and an entire apple orchard were trucked in on flatbeds to give the feeling that the landscape had always been there. The installation of the entry driveway and forecourt, formal rose garden, brick walks and weeping cherry trees was also completed at this time.

1959: The Lila Wallace Touch, the Interior Design of the House

At this time, Mrs. Wallace also brought in William Kennedy and Benjamin Garber, the interior designers who decorated the offices for The Reader’s Digest, to furnish the house. Their intent was not to accurately furnish the interiors of Boscobel based upon historical research. Instead, they tried to create elegantly decorated rooms that complimented the beauty of the architecture. Also, because States lived in England for such a long time, they also deemed it would be appropriate to furnish the house mainly in eighteenth-century English and European antiques, which they acquired over several years both in America and abroad, selecting and assembling appropriate personal and household effects for each room.

They also chose blue as the dominant color, providing a consistent palette throughout the interior. It was also used in a slightly muted version on the exterior with a contrasting white trim on the woodwork. This choice may have been inspired by the classical design and the color scheme of the Jasperware tea service Dyckman purchased from Wedgwood and Byerley, London, on August 29, 1803. But it also did not hurt that blue was Mrs. Wallace’s favorite color. Although the results of their decorating were beautiful, and are still fondly remembered by some of Boscobel’s early visitors, it was more of a decorator’s showcase than an accurate historical restoration.

1961: Boscobel Opens to Critical Acclaim

On May 21, 1961, the restored home of States and Elizabeth Dyckman was formally opened to the public. A large tent was erected on the front lawn and, in addition to Mrs. Wallace and the board of directors, many dignitaries were present. In his keynote address, Governor of New York, Nelson A. Rockefeller, referred to Boscobel as “one of the most beautiful houses ever built in America.”

Continuing her personal involvement, in September 1962, Mrs. Wallace hosted a party to unveil the new docent uniforms created by well-known New York designer, Mainbocher. The uniforms were created in a shade called “Boscobel blue” which was in keeping with the interior decor of the house.

1964: Tradition of Public Events Begins at Boscobel

On July 16, 1964, a black-tie party was hosted by the Wallaces to preview the newly developed “Sound and Light” program at Boscobel, which she had funded. The forty-minute program was narrated by Helen Hayes and Gary Merrill and dramatized the discovery and development of the Hudson River beginning with Henry Hudson and ending with the restoration of the Boscobel mansion. The program became a permanent feature at Boscobel until the mid-1970s, with two evening performances a week scheduled throughout the summer.

Mid-1970s: New Scholarship Brings New Interpretation

In the mid-1970s, the original 1806 inventory of the house was discovered. This led to the decision to totally redo the interiors of the house so they were more historically accurate. Lila Wallace magnanimously agreed to sponsor the changes. Berry B. Tracy, Curator-in-Charge of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was hired as a consultant to research the new interiors and oversee the installation. Mr. Tracy worked closely with Frederick W. Stanyer, then executive director of Boscobel. The English pieces were replaced by an outstanding collection of Federal period furniture made mostly in New York City. The reproduction carpets, paint colors, wallpaper, fabrics and window treatments used were all based upon documented period examples.

1977: Boscobel Reopens to Critical Acclaim

When the house reopened to the public in June 1977, after six months of intense restoration work, Boscobel was featured in a cover article by Rita Reif in the Home Section of The New York Times on July 21, 1977. The headline read, “The Tour de Force Of Redecorating Boscobel.”

Boscobel Today

Celebrating its sixth decade as a Historic House Museum, Boscobel continues to evolve. In 1989, the 1824 inventory of the house was discovered. The information contained in this extremely valuable resource combined with other more recent research projects continues to inform the interpretation of Boscobel and provide guidance in making updates and improvements to the mansion’s furnishings and the property. The result is that Boscobel is not a house frozen in time but a dynamic, engaging place.

The house and grounds remain alive through innovative programs such as special tours, workshops and exhibitions. The gardens and pathways continue to encourage renewed interest in the landscape of the Hudson River Valley. Indeed, no other house has traveled–figuratively and literally-such a road to revival.